It All Begins with The Division of Labor

Meditations on what should be the central insight of economics

In 1776, Adam Smith wrote a book entitled An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, asking one of the most important questions about human society: why are some societies wealthy and others poor? His answer is the very first sentence of the 1,000 page tome:

The greatest improvement in the productive powers of labour, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgment with which it is any where directed, or applied, seem to have been the effects of the division of labour.

Of course, we need to unpack just what exactly “the division of labor” means, and its relationship to economic growth & human progress. Smith is far from the first thinker to recognize that societies divide their labor, or that more advanced societies tend to have more division of their labor. Arguably a better description of the division of labor is the 15th century Arab thinker Ibn Khaldun, who wrote:

The individual being cannot by himself obtain all the necessities of life. All human beings must co-operate to that end in their civilization. But what is obtained by the cooperation of a group of human beings satisfies the need of a number many times greater than themselves. For instance, no one by himself can obtain the share of the wheat he needs for food. But when six or ten persons, including a smith and a carpenter to make the tools, and others who are in charge of the oxen, the ploughing of, the harvesting of the ripe grain, and all other agricultural activities, undertake to obtain their food and work toward that purpose either separately or collectively and thus obtain through their labour a certain amount of food, that amount will be food for a number of people many times their own. The combined labour produces more than the needs and necessities of the workers. (Prolegomena The Muqaddimah).

You could also find the insight in Plato:

A state…arises, as I conceive, out of the needs of mankind; no one is self-sufficing, but all of us have many wants…Then, as we have many wants, and many persons are needed to supply them, one takes a helper for one purpose and another for another; and when these partners and helpers are gathered together in onehabitation the body of inhabitants is termed a State…And they exchange with one another, and one gives, and one receives, under the idea that the exchange will be for their good. (Republic, p. 60)

What is unique in Smith, arguably, is that he does not merely describe the division of labor, but makes it the centerpiece of a systematic vision of how society works, how economies grow, and gives an analytical account of the causes and consequences that the division of labor has on human cooperation and progress.

Economists since the 20th century generally start their analysis, by contrast, with an economic model of an individual — Robinson Crusoe marooned on a deserted island is the favorite literary analogy — choosing how to optimally allocate their scarce resources. Indeed, the famous 1932 definition of economics from Lionel Robbins is “the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.” Should we be able to fully specify a utility function for said individual, there is actually no economics here: the “problem” is a technological one, an engineering exercise, a mere math problem. There is no genuine human choice here, only an optimization problem where the calculus derives “the” optimal course of action for the individual. (More on this in future posts). Regardless of the validity of this starting point, it can correctly show the stark limitations of self-sufficiency: assuming no magical manna from heaven, anything and everything Crusoe wishes to consume he must first produce by himself.

As the John Donne poem goes, no man is an island. It is only once we have multiple people associating and interacting with one another that we begin to confront genuine economic issues. James Buchanan argued in one of my favorite papers that the study of economics really should begin with exchange, and gravitate around this central theme, rather than resource allocation.

Likewise, I argue that division of labor is one of the central, perhaps the central insight of economics, and so much about our exchange behavior and its implications for human society can be understood through it. We can apply its implications to learn important insights about international trade, globalization, industrial organization, antitrust, and many other issues (many of which I plan to blog about). Its place in the economics curriculum is massively underrated (if it is mentioned at all), whereas I think it should be one of the starting lessons. In many of my courses, it is what I cover on the first day of class.

It helps us resolve the basic tension between three facts that motivate economic analysis:

People pursue their own separate goals (I prefer this over loaded terms like “rationality” or “self-interest”)

We live in a world of scarcity (where we don’t have enough resources to satisfy every person’s every goal)

We live in a functioning, complex, social order (that is, we are able to sustain 8 billion people on the planet)

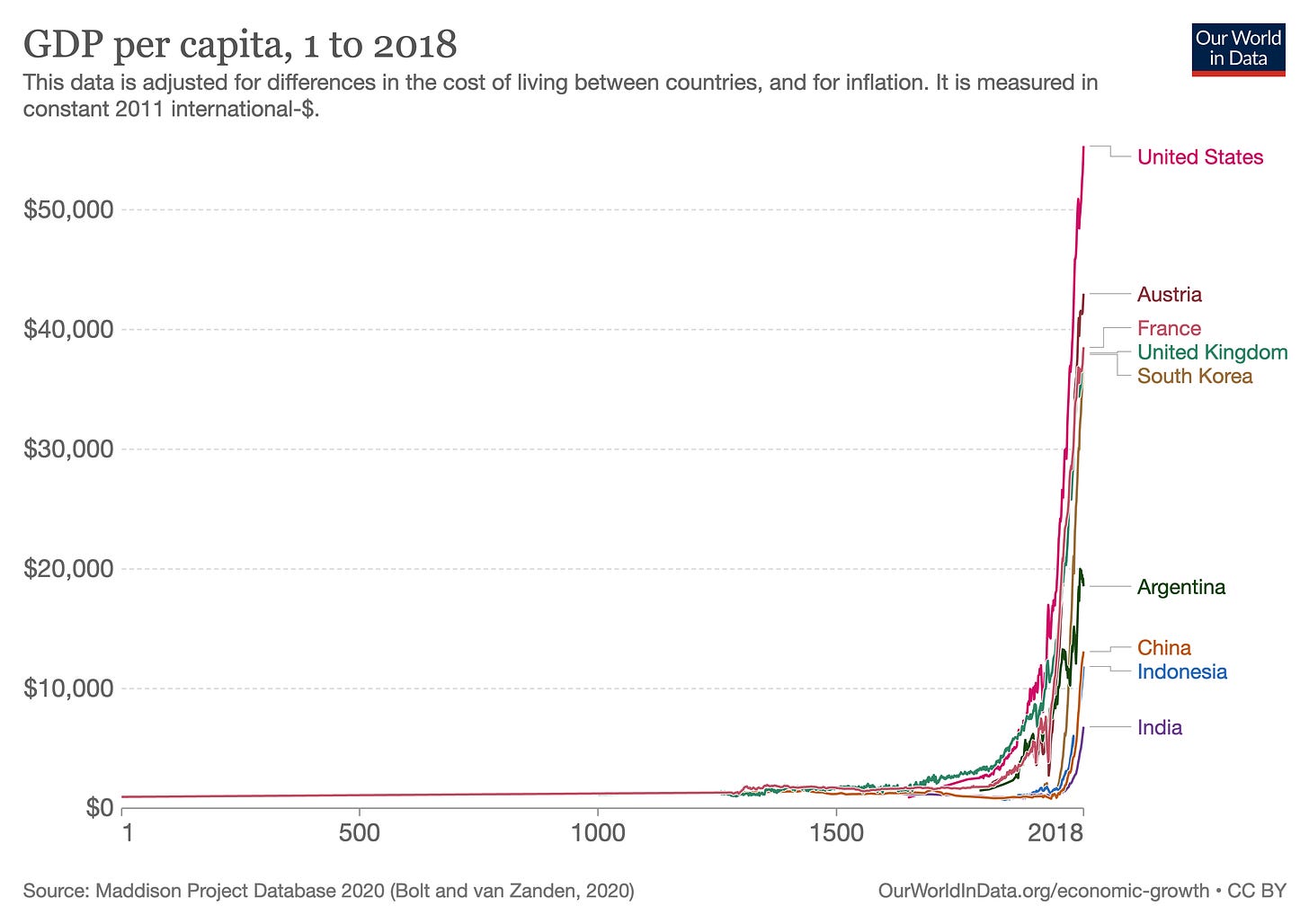

And finally, we can’t forget “the great fact” of the “hockey stick” graph of human progress, as Dierdre McCloskey calls it:

Smith wrote just before the takeoff would occur, so he wasn’t able to look to the right of 1800 on the graph. But what he wrote about helped explain the uniqueness of modern society, what he called a “commercial society,” and how it worked.

Specialization and Exchange

If it is so important, just what exactly does “division of labor” or “dividing up labor” mean? I interpret and paraphrase the concept as specialization and exchange. Specialization and exchange describes what is really occurring when we have certain people perform certain tasks, rather than every person producing everything they need. I tell my students that you can both explain the essence of economics, and the answer to the great question of why some countries are rich and other are poor, by understanding all of the implications of the idea of ever-increasing specialization and exchange. For this reason, I have been intrigued by Arnold Kling’s approach to "reintroduce" economics as the study of patterns of sustainable specialization and trade (PSST). While descriptively rich, I yearn for a snappier phrase, and hence stick with “specialization and exchange.”

The division of labor is not a novel concept. Ancient societies had division of labor. Pretty much every human society — including groups of hunter gatherers before they settled down into established civilizations — has had division of labor to some degree. It might be very rudimentary, with very few specialties or roles: for example, some hunt, some gather. In post-Neolithic societies, most people might be farming merely to survive, as did the average human being for thousands of years; but there might still be a division of roles on the farm, and some whose primary role is not farming, but making relevant equipment, smithing, weaving various clothing, or perhaps even crafting some luxury goods.

This again suggests why many philosophers, including Plato and Ibn Khaldun mentioned above, recognized the existence and (to a lesser degree), the importance of the division of labor and hence commented on it. But here, simply the mere act of dividing up jobs, or assigning people to various roles and tasks, does not capture the implications of the idea: there may be specialization, but there is not (market) exchange.

Economist P.T. Bauer summarized economic development the process of converting production for subsistence to production for exchange. That is to say, rather than producing (often farming) to feed yourself or satisfy your needs, you produce primarily to sell your produce to others. Those sales earn you income, which you can then use to acquire all of your other needs (food, clothing, housing, transportation, luxuries, etc) via exchange, rather than making them yourself.

Market-oriented economists and advocates of extensive state economic

control are agreed on one matter, namely that advance from subsistence

production to wider exchange is indispensable for a society’s escape from

extreme poverty. In the absence of opportunities for exchange, there is little

scope for the division of labor and the emergence of different crafts or skills. (Bauer, 2000, p.7).

Teamwork Makes the Dream Work

So we know that division of labor is important, but why does it improve the wealth of nations? The primary consequence is that production performed under the division of labor vastly exceeds that of self-sufficient production. The famous example given by Smith is the pin-factory:

To take an example...from a very trifling manufacture...the trade of the pin-maker. [I]n the way in which this business is now carried on, not only the whole work is a peculiar trade, but it is divided into a number of branches, of which the greater part are likewise peculiar trades. One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head...and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations...Ten men only were employed [and they] could make among them upwards of forty-eight thousand pins in a day...But if they had all wrought separately and independently [they] certainly could not each of them have made twenty, perhaps not one pin in a day... (Book I, Chapter 1).

I’ve referred to this in my introductory post, claiming that people unfortunately bastardize and reduce the idea of the division of labor down to a claim that “assembly lines are more productive.” I think taking a more holistic account of the causes, consequences, and implications of the division of labor — a glimpse of which I’ve tried to capture in this post — demonstrates Smith had the big picture of society in mind, rather than the productive efficiency of a factory system.

My own preferred example that better encapsulates the division of labor is Smith’s discussion of the woollen coat, as it brings to the foreground the untold cooperation of vast quantities of strangers across the world (more about this in the next section):

Observe the accommodation of the most common artificer or day-labourer in a civilized and thriving country, and you will perceive that the number of people of whose industry a part, though but a small part, has been employed in procuring him this accommodation, exceeds all computation. The woollen coat, for example, which covers the day-labourer, as coarse and rough as it may appear, is the produce of the joint labour of a great multitude of workmen. The shepherd, the sorter of the wool, the wool-comber or carder, the dyer, the scribbler, the spinner, the weaver, the fuller, the dresser, with many others, must all join their different arts in order to complete even this homely production. How many merchants and carriers, besides, must have been employed in transporting the materials from some of those workmen to others who often live in a very distant part of the country! how much commerce and navigation in particular, how many ship-builders, sailors, sail-makers, rope-makers, must have been employed in order to bring together [resources] from the remotest corners of the world! What a variety of labour too is necessary in order to produce the tools of the meanest of those workmen! To say nothing of such complicated machines as the ship of the sailor, the mill of the fuller, or even the loom of the weaver, let us consider only what a variety of labour is requisite in order to form that very simple machine, the shears with which the shepherd clips the wool. The miner, the builder of the furnace for smelting the ore, the feller of the timber, the burner of the charcoal to be made use of in the smelting-house, the brick-maker, the brick-layer, the workmen who attend the furnace, the mill-wright, the forger, the smith, must all of them join their different arts in order to produce them…If we examine, I say, all these things, and consider what a variety of labour is employed about each of them, we shall be sensible that without the assistance and co-operation of many thousands, the very meanest person in a civilized country could not be provided, even according to what we very falsely imagine, the easy and simple manner in which he is commonly accommodated, (Book I, Chapter 1).

Regardless of the famous examples, which do capture the imagination, the big question is why is division of labor more productive than if we all had wrought separately and independently? Smith gives three famous reasons:

This great increase of the quantity of work which, in consequence of the division of labour, the same number of people are capable of performing, is owing to three different circumstances; first to the increase of dexterity in every particular workman; secondly, to the saving of the time which is commonly lost in passing from one species of work to another; and lastly, to the invention of a great number of machines which facilitate and abridge labour, and enable one man to do the work of many, (Book I, Chapter 1).

First, the division of labor increases what Smith calls “dexterity.” This is referring to the fact that if a worker specializes on one or a small set of tasks and their job consists of them doing this repetitively, it tends to improve their skills at those tasks. These skills make workers more productive and efficient, thereby producing more output with less input or effort. Doing something many times might cause you to find shortcuts to get the work done faster, or with less effort (either way, this saves resources). Bill Gates is supposed to have said “I choose a lazy person to do a hard job. Because a lazy person will find an easy way to do it.” You might also develop habits and skills by recognizing general patterns of problems that crop up, and common ways to solve them. In general, we can call this idea “learning by doing.” The more you work on something, the more effective you get at producing it.

Second, by having people focus only on a small range of tasks, the division of labor saves the time wasted from switching between tasks. This one is pretty straightforward.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the division of labor facilitates invention and the use of capital that often saves labor and makes it more productive. This might be a physical extension and embodiment of the worker’s “dexterity” where workers “on the ground” discover new ways of doing things and rig together tools, routines, or devices to make their work faster or use fewer resources. At a more general level, division of labor is what makes innovation and invention economical: increasing returns to scale and economies of scale (the theme of this blog). I discuss this in the final section.

The Result of Human Action but not Human Design

One of Smith’s more unique insights is that ordering of social cooperation under the division of labor is spontaneous, not centrally-directed. This is perhaps the most difficult fundamental insight of social science for non-economists (and even some economists):

This division of labour, from which so many advantages are derived, is not originally the effect of any human wisdom, which foresees and intends that general opulence to which it gives occasion. It is the necessary, though very slow and gradual, consequence of a certain propensity in human nature which has in view no such extensive utility; the propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another (Book I, Chapter 2).

While memorably described by Smith, my favorite summary of this comes from another 18th century Scot named Adam: Adam Ferguson’s phrase that many social institutions are “the result of human action but not the execution of any human design.” Many of the provocative examples that economists love to give when hoping to stimulate interest in economic thinking derive from this discovery; for example, the fact that no single person on earth has the knowledge and ability to produce even a pencil (now in video). Or a toaster.

Many of the ancient philosophers that have commented on the division of labor — Plato comes chiefly to mind — seem to consider the division of labor as something that can be directed and molded from the top-down. Indeed, Plato’s vision of the ideal State in The Republic features a “noble lie” to create and sustain the division of society into different social classes for the purpose of preserving order and justice (“the goal” of society).

It is mind-bendingly difficult to try reconcile the complexity and apparent chaos of human society with a pattern or principle that the mind can comprehend.1 Historically, the solution was to appeal to religion — the complexity of society is actually designed or at least guided by the divine. While computationally and mentally easy to grasp, this explanation created opportunities for “prophets” claiming to understand the overarching scheme of society and have secret access to “the plan” for society or history, enabling them to seize control of society via the State to bring it about. With the Enlightenment, dissatisfaction with religious explanations (and also their capture of political power) gave way to the secular ideologies of capital-R Reason (Descartes, Comte, etc), or capital-H History (Hegel, Marx, etc) as a means to explain “the plan” for society (enabling them to seize control of society via the State to bring it about).

Recognizing the spontaneous ordering of social cooperation under the division of labor allows us to reconcile the complexity of society with clear patterns we can reasonably understand: There is no single goal for Society that we all must submit to but many goals for the many separate persons who must find ways to live together peaceably and productively in order to flourish. This is the essence of liberalism, and our imprative is to discover the rules that allow us to do this without dominion or discrimination (or ripping each other’s throats out) — chief among these is specialization and exchange (and institutions that facilitate them like property rights and market prices).

Smith, however, highlights the importance of spontaneous order in markets and other aspects of human society. I think it’s also safe to interpret Smith as saying that exchange is (part of) what makes us human:

Whether this propensity be one of those original principles in human nature, of which no further account can be given...It is common to all men, and to be found in no other race of animals, which seem to know neither this nor any other species of contracts...Nobody ever saw a dog make a fair and deliberate exchange of one bone for another with another dog...Nobody ever saw one animal by its gestures and natural cries signify to another, this is mine, that yours; I am willing to give this for that. (Book I, Chapter 2).

When looking at a large modern society, self-sufficiency, Robinson Crusoe-style, becomes impossible. Or, at least, it’s certainly not possible to have a comparable standard of living today by producing everything yourself (some of us might be able to eke out a life at a mere subsistence level). Contrary to our more romantic notions of independence, autonomy, self-reliance, and a closeness to nature, this interdependence has tremendous upsides, but calls for organizing principles altogether different than what we, as a species, are used for nearly all of our evolutionary history:

In civilized society [man] stands at all times in need of the cooperation and assistance of great multitudes, while his whole life is scarce sufficient to gain the friendship of a few persons...man has almost constant occasion for the help of his brethren, and it is in vain for him to expect it from their benevolence only.

Whoever offers to another a bargain of any kind, proposes to do this. Give me that which I want, and you shall have this which you want...and it is in this manner that we obtain from one another the far greater part of those good offices which we stand in need of. It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. (Book I, Chapter 2).

Much like the historical tribes our distant ancestors belonged to, we belong to groups of friends, family, and peers where we can depend on one another’s services out of love, duty, or obligation. But not in a modern society of strangers. I can count on my friends or family for a couch to crash on if I show up unannounced, no payment necessary (in fact, it would be offensive to them); but I can’t do that in a new city where everyone is a stranger to me. Dunbar’s number of about 150 supposedly describes the upper limit of the number of people we have the ability to recognize and maintain active relationships with. The population of the U.S. is over three hundred million and the population of earth is now nearing eight billion. Most of the people you interact with in your life, and in nearly all commercial transactions, are people you don’t know, and will never meet. Thus, to understand how we interact with one another as strangers, we need to understand mutually beneficial exchanges.

Famously, Darwin’s theory of evolution in biology came about by his reflections on Smith and Malthus’ discussions of the spontaneous order of human society a century earlier.

DOL is the Cause, Not the Consequence of Specialization

One other counterintuitive insight of Smith’s is that the division of labor is what causes us to specialize in various tasks or careers, not the other way around! It’s easy to think that I am an economics professor because I am naturally talented at it, or that Lebron James is a basketball star because he is naturally talented at it (OK, his height certainly helps). Most of this is ex post rationalization to justify our specializations; it might be true that we have grown to be better at our specializations (for the reasons described by Smith that I discuss in the next section), but it is probably not the cause in most cases.

It is easy for people who understand a little bit (or even a lot) of economics to think of the idea of comparative advantage here: it is more efficient for people (or countries) to specialize in producing only what they have the lowest opportunity cost in producing, and then exchanging for everything else. Comparative advantage is indeed a powerful, counterintuitive, and beautiful concept — another valuable insight in economics; but comparative advantage really is just a particular aspect of the division of labor in time (expect a future post on this). I again submit that division of labor remains the more fundamental explanation, since comparative advantage is actually endogenous, one’s comparative advantage is at least in part determined by the division of labor at any point in time.

We can begin to understand this with Smith’s provocative consideration about the distribution of natural talents:

The difference of natural talents in different men is, in reality, much less than we are aware of; and...is not upon many occasions so much the cause, as the effect of the division of labour. The difference between the most dissimilar characters, between a philosopher and a common street porter, for example, seems to arise not so much from nature, as from habit, custom, and education....[F]or the first six or eight years of their existence, they were perhaps, very much alike...About that age, or soon after, they come to be employed in very different occupations. The difference of talents comes then to be taken notice of, and widens by degrees, till at last the vanity of the philosopher is willing to acknowledge scarce any resemblance. But without the disposition to truck, barter, and exchange, every man must have procured to himself every necessary and conveniency of life which he wanted. All must have had the same duties to perform, and the same work to do, and there could have been no such difference of employment as could alone give occasion to any great difference of talents…As it is this disposition which forms that difference of talents, so remarkable among men of different professions, so it is this same disposition which renders that difference useful. (Book I, Chapter 2).

Comparative advantage, and in general, our skills, talents, and specializations, are largely determined by the division of labor at any point in time. And now we must turn to what determines the division of labor at any point in time: scale.

Size (of the Market) Matters

One of Smith’s greatest insights, and perhaps the most consequential chapter title in the book is that the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market.

As it is the power of exchanging that gives occasion to the division of labour, so the extent of this division must always be limited by...the extent of the market. When the market is very small, no person can have any encouragement to dedicate himself entirely to one employment, for want of the power to exchange all that surplus part of the produce of his own labour, which is over and above his own consumption, for such parts of the produce of other men's labour as he has occasion for, (Book I, Chapter 3).

This is the theme of this blog, the general nature of increasing returns to scale (at the market level): the larger the number of exchange opportunities with people (i.e. “the market,” for convenience), the greater the social returns to specialization and exchange. As Smith states, if our society were a small isolated island of a hundred people, there would be division of labor, and there would be specialization and exchange, but specializations would be very crude and shallow. Some of us might hunt for food, some of us might make clothing, some of us might build shelters, and so on, as we focus on the primary goals of survival. Nobody would specialize in being a concert pianist, or a video game designer.

Things are radically different, however, as markets grow larger. In a globalized world of seven billion people, it now does pay to specialize in a career in concert pianist, or video game design (at least in an absolute sense; perhaps not in a relative to careers in, say finance or software engineering - also uneconomical in a society of 100 people!)

As a further example, it would make sense for one or a few of us to specialize in medicine and be the village doctor in our tiny island. Their knowledge of medicine would have to wide-reaching but shallow. They would need to know just enough to treat all of the ailments we have: from how to set a broken arm to treating influenza to birthing babies. In today’s globalized society, one does not merely become a doctor, one specializes in a particular branch of medicine: cardiology, neurology, OBGYN, ENT, oncology, family medicine, etc. Likewise, an aspiring engineer must choose to focus on civil, electrical, mechanical, biomechanical, and other engineering specializations. Such specialization allows us to discover deeper insights into how things work and how to improve them, and then they can be shared with everyone. None of this would be possible if the market were not large enough to support it.

We should note that it’s not merely population (i.e. having a “big country”) that matters here, it is exchange opportunities in markets. The citizens of a tiny but globally-connected country can enjoy higher standards of living than a “large” but isolated one. Singapore and Luxemborg both have higher income per person than the United States, China, and Russia. Modern endogenous growth models like Paul Romer’s famous 1990 paper (where people are able to invest in the production of ideas that can benefit everyone as a public good) reach the same conclusion: “If access to a large number of workers or consumers were all that mattered, having a large population would be a good substitute for trade with other nations,” (p.S98).

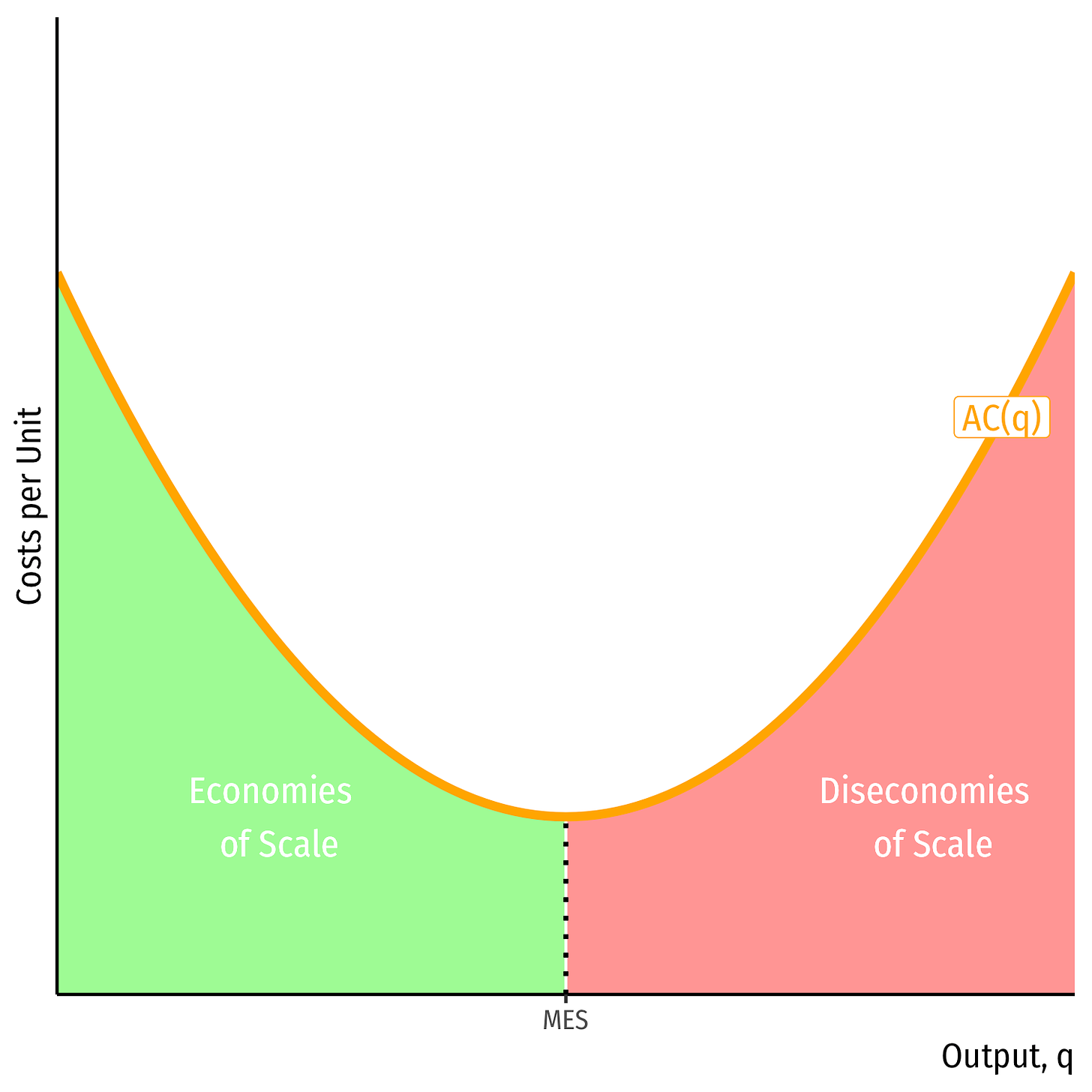

The important economic concept that this implies is economies of scale: producing and selling more lowers cost per unit. The reason is that since you are able to produce and sell for a larger and larger group of customers, investment in fixed capital (which improves labor productivity) is spread over a larger volume of output, lowering per-unit costs. This is a major explanation for Adam Smith’s third effect on productivity: invention and innovation become profitable at larger scales of production. It’s also the reason that people misunderstand the pin factory example — building a factory or an assembly line is not always the answer! Allyn Young points out in one of my favorite papers on the topic that “[Henry] Ford's methods would be absurdly uneconomical if his output were very small.” Building a $100 million car factory to sell cars to our 100 person island would yield an average fixed cost of $1 million per car (ignoring the other resource costs)! But that same car factory selling to a globalized market of, say 1 million people would yield an average fixed cost of just $100 per car.

If you’ve made it this far, congratulations and thank you! I apologize for the sparsity of posts (my family got Covid soon after I published the first post and I’ve been playing catching up since). In this post, I have tried to plant the intellectual roots of future applications and explorations in the idea of increasing returns arising from the division of labor. I hope to continue weekly explorations of these issues.

I thank a conversation with Vlad Tarko for a lot of the thoughts in this paragraph.