Economics as a Foreign Language

One Explanation for Why So Many People Just Can't "Get" Economics

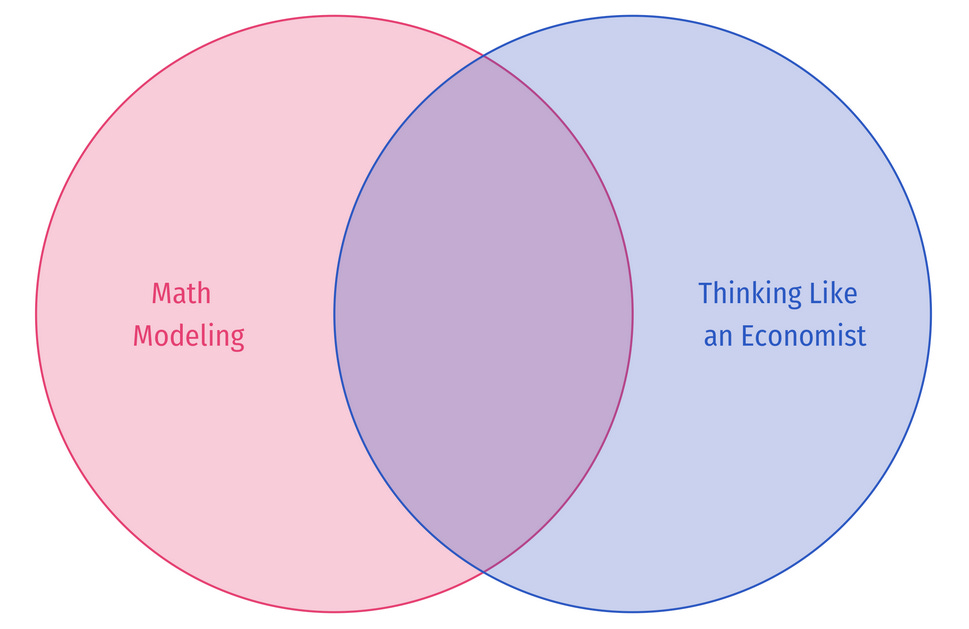

It’s the start of another semester, and I’ve been thinking a lot about why people are apprehensive or even resistant to economics, let alone struggle with it. It’s not just the math — which, of course, is a major hurdle for a lot of people unfortunately — but as I explain to my students, there’s a lot more to the economic way of thinking than just mathematics and modeling. I like showing the following Venn Diagram:

In any case, I’ve come to realize after teaching it for 10 years that one of the fundamental problems and disconnects that people have with economics is that it’s like a foreign language. Or at least, we should think about it like we think about learning foreign languages, and that will alleviate many of the issues that people have with it.

The bigger problem, is that unlike Spanish or Russian, this language sounds a lot like English (assuming English is what you speak). Economists use terms like “cost,” “profit,” “efficiency,” “welfare,” “public good,” “technology,” and “capital.” For each of these words, everyone with a basic grasp of language and lived experience has a good working definition. All of us navigate life and interact with others using these terms. You can’t get far in life without knowing what “cost” or “efficient” means! And when in doubt, look in the dictionary.

The problem is that all of these words, and some others, economists use in a very different way than in ordinary language (and it won’t show up in the dictionary definition).1 For example, all costs in economics are opportunity costs; and profits in economics include opportunity costs. And public goods aren’t “what governments provide,” it’s goods that are nonrival and nonexcludable. And let’s not get started on what economists mean by efficiency.

In fact, a good handful of drafts I am preparing for this newsletter are just long disquisitions on what we mean by things like “capital” and “technology.” On these ideas, I’ve always wanted to compile my thoughts on working definitions and applications for these terms that I can point people to, instead of some hand-waiving about “well, let’s just simplify and call it machines for right now, etc.”

To make matters worse, thinking through an economic issue using the everyday meanings of these words can lead to mistakes, sometimes critical ones. A company earning a profit on paper (what economists call “accounting profits”) may in reality be earning a loss in an economic sense.

Like any language, there are also new terms and vocabulary that don’t translate out of the vernacular very well. Economist are known, for better or worse, for throwing around very technical phrases and jargon. My wife (who is an attorney, for context) often jokes that economists are just people who make up new words for things that people already know. There is definitely some truth to this, which is why I find it funny. But I would also argue that so long as we don’t overdo it just to sound smart, there is enormous value in words economists have made up. Most of them start with the word marginal — marginal benefit, marginal cost, marginal rate of substitution, marginal rate of transformation, etc.

Finally, there is also an enormous problem connected with the fact that economics is a foreign language that sounds like English: everyone thinks they are already an economist, to some degree.

Again, you can’t get far in life without knowing and using ideas about cost, efficiency, etc. And all of us are consumers, interact with producers, vote for elected officials, pay taxes, and enjoy public services and are subject to regulation. So it’s only logical that most people have opinions about taxes, welfare programs, trade protectionism, immigration, and so on. Most of it is of course, bad — in that it’s the more result of biases, ideology, and politicking. But most people can recognize the role of self-interest and dollars-and-cents cost-benefit analysis. But again, use the wrong (every day) meanings of otherwise normal words, and make important mistakes.

A lot of economic conclusions are, to be fair, just common sense. If the price of bread increases, people are going to tend to buy less bread. But economists reach this conclusion — an implication of the law of demand — through rigorous chains of logical reasoning encapsulated in models. There’s a lot to criticize in how this is done (that’s half of my posts in this newsletter! though I hope the other half are ideas for improvement). But it’s how economists see, understand, and explain the world. I borrow Peter Boettke’s great line that I am not a “9 to 5 economist” — I don’t stop being an economist when I go home: it’s still how I see the world and make it intelligible.

So this may be why it’s so difficult for people to grasp. It’s not like some other disciplines where if you can just memorize a bunch of facts or absorb the terms by osmosis, you can eventually “get it.” With economics, you are literally re-wiring your brain to process the world in a different way. It’s a way of thinking about the world in terms of a few core principles (models) and applying them carefully but ruthlessly. I can’t just stop seeing the world in terms of incentives, opportunity costs, and equilibria because my workday is finished!

Though that might be a good project to compare dictionary definitions and economic definitions. There are some great economic dictionaries/encyclopedias out there too. Here’s my favorite free one.