Globalization and the Political Challenge of Markets

How the Division of Labor Successfully Creates Wealth and Destroys Jobs

In some of my previous posts, I explored the idea of the division of labor in Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations as one of the central insights of economics. Smith of course was writing in 1776, before the Industrial Revolution really took off. However, we can extrapolate many of his insights to help understand the dynamics of the modern, post-industrial-revolution world.

The two main insights that I want to track are the idea that the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market, and that expanding the division of labor makes us more productive with more viable capital investment. In modern parlance, there are economies of scale: the bigger an operation is, the cheaper per unit it is to produce. At smaller scales of operations, while it might be technologically feasible, it is not economically viable to employ lots of capital (a factory, assembly line, robots, etc). Larger scale operations render investment in capital more profitable since the fixed costs of the investment (e.g. building the factory) can be spread across a much larger volume of output (and hence, lower fixed costs per unit — and if the fixed costs are large relative to variable costs, total average cost is lower as a result). The consequential insight to add here is how this process of extending the market affects labor, or more to the point, jobs.

If you took a time machine back to the year 1790 at the founding of the United States, the total population was about 3 million people, 90% of whom worked in agriculture. Moving forward to the turn of the 20th century, the population grew by an order of magnitude to 76 million people, about 40% of whom worked in agriculture. Fast forward to present times, where there is yet another order of magnitude of population, around 325 million people, less than 1% of whom work in agriculture (according to the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service).

Suppose someone stowed away in your time machine in 1790 and rode back with you to the present. After they learn about these statistics, they would have two questions:

Why isn’t everybody starving?

Why isn’t everybody unemployed?

We’ve gone from a country where nearly everybody worked in farming in order to support a population of a few millions, to one where almost nobody works in farming anymore, yet there is a population 100 times as large!

The Market Giveth (Wealth), The Market Taketh Away (Jobs)

The ultimate goal of economic activity, Adam Smith reminds us,1 is consumption. I hasten to remind us that this does not merely concern material wealth—things—but the ability to live a good and flourishing life, however one defines it. But as we live in a world of scarcity and not in Eden, wealth must first be produced before it can be consumed. At a 10,000 foot level, the idea of a job is just taking lower-valued resources and adding value to them to create higher-valued goods that ultimately (perhaps after several transactions down the chain), will lead to something someone somewhere can enjoy for some purpose of their own. A job, or production more broadly, is merely an instrumental means to the ultimate and diverse ends of consumption.

Think about how economists define the idea of economic growth, doing more with less. That means obtaining more outputs with fewer inputs, growing more food with fewer farmers, making more cars with fewer manufacturers, and so on.

Of course, what happens is that as markets get larger (i.e. the number of people that can exchange with one another), there are greater efficiencies that arise from specialization and from larger operations. Investing in a large factory or robots makes little economic sense, even if it were technologically feasible, when you can only sell your product to a few

other people. Factories, robots, and other capital investments are essentially a massive fixed cost. That one time cost can only be spread across a small volume of output, so the average cost per unit sold is very high. Imagine a factory costs $1 million to build. Ignoring all other production costs, if you are able to sell 1,000 units, that’s still a cost of $100,000 per unit. Whereas, if you can sell 100,000 units, then that’s a cost of $1,000 per unit. These economies of scale become quite significant as the market gets larger. Thus, again, Adam Smith’s insight about the productivity of pin factories due to the division of labor is more about the economies generated by the extent of exchange opportunities, rather than anything inherent in factory organization.

However, the key issue here is that in production, capital is a substitute for labor. As the scale of operations increases (because of the extent of the market), the per unit cost of investing in capital decreases. More capital (let’s interpret it simply as “tools” or “machines” for now) makes existing labor more productive, which means either that you can produce more output with the same amount of labor, or you can produce the same amount of output with less labor.

If you want to dig a ditch, there are a number of ways you might do this. Consider three:

You can hire 100 people with sticks (or perhaps just their bare hands).

You can hire 10 people with shovels.

You could hire 1 person with a backhoe.

Note the key differences at each “stage” or “scale” of production in terms of (a) employment, (b) labor productivity, and (c) use of capital. One hundred workers means one hundred jobs for the task. But each worker, with a stick at best or bare hands at worst, is not very productive (that’s why you need a hundred of them). As such, the wage paid to each worker will be very low. Ten workers with shovels means each worker is more productive, having been augmented with tools & capital, and thus can command a higher wage. But you need far fewer of them to get the same job done. Finally, one person with a backhoe will be enormously productive such that you only need them — and they need to be skilled enough to operate and maintain the complex machinery, so their wage will be relatively high.

For most of civilization, only the first two methods were available, at best: specialization was at a level sufficient for people to invest in crafting only crude tools to ease their labor — sticks, shovels, and other basic implements. Even if were somehow technologically feasible (and of course, it wasn’t until the 20th century), there was no economic rationale to invest in capital like factories or diggers or machines since the market was very small. Investments in capital could not be spread across a large enough volume of output to lower costs (and thus, prices to buyers as well).

My oft-used example of the ditch reminds me of the famous story about Milton Friedman visiting China in the 1980s: upon touring a site where many workers were digging up the earth for a construction project, Friedman asked why don’t they use modern machinery like tractors. The response given to him was that this would lead to fewer jobs. Recognizing the true, if unspoken goal of the program was to create jobs, rather than build infrastructure efficiently, he asked his host “why don’t you give them spoons instead of shovels” and thus create even more jobs.

So here again is the crux: as exchange opportunities expand, the gains to specialization increase, and so do the rewards to substituting capital for labor within an industry. Employment, i.e. the number of jobs, in an industry will initially increase with greater demand from a larger market of consumers, but then ultimately decrease if each worker gets more productive (and wages increase) with more capital invested.

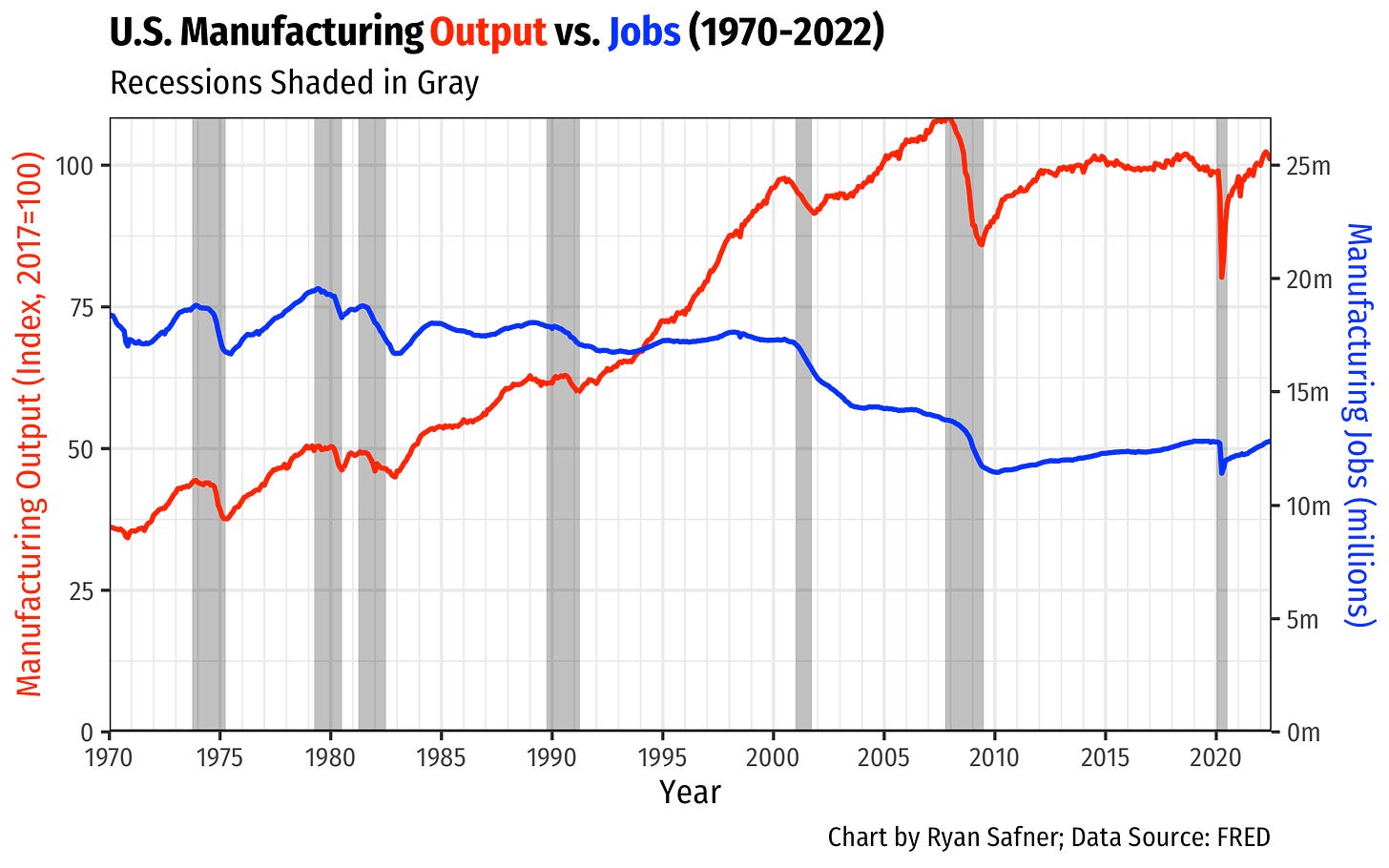

If, for example, we look at the U.S. manufacturing industry — something that politicians and voters have been lamenting for decades, is the decline of manufacturing jobs. Manufacturing jobs peaked in the late 1970s, well before NAFTA, the trade shock with China, and other political bugaboos. However, output, and productivity, aside from the 2008 financial crisis and COVID-19, have only been trending upward.

So we return to a fundamental political economic dilemma: markets create wealth but destroy jobs over time.

Creative Destruction Creates and Destroys

One of the fundamental insights about the market process comes from Joseph Schumpeter, the famous idea of “creative destruction:”2

“Capitalism...is by nature a form of economic change and not only never is but never can be stationary...The essential point to grasp is that in dealing with capitalism we are dealing with an evolutionary process…”

“The fundamental new impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in motion comes from the new consumers’ goods, the new methods of production or transportation, the new markets, the new forms of industrial organization that capitalist enterprise creates...that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one. This process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism. It is what capitalism consists in and what every capitalist concern has got to live in,” (pp.82-83).

Horses and buggies give way to the automobile, typewriters and secretaries to laptops and calendar management software. In general, we consider this progress.

This is also the response to our time-traveler’s second question from above. The reason there are so few jobs in farming today relative to everything else is that there are so many other new industries. The alternative to farming is not unemployment, but employment among countless other industries that did not exist previously. Once we got productive enough at farming with mechanization and new scientific discoveries, farmers became so productive we did not need as many. And with access to calories becoming cheaper, we could specialize and create new industries. Millions of people moved from the countryside (or other countries) into to the cities to find new opportunities in booming new industries: manufacturing, railroads, the automobile, petrochemicals, aviation, telecommunications, semiconductors, the internet, software engineering, etc. None of them, by the way, would have been possible were it not for the greater extent of the market and the gains to specialization — we would all be back subsisting on the farm, like our ancestors.

However, we cannot ignore the costs of this: there is the destruction part of creative destruction to worry about. It would be tough to be a horse-and-buggy manufacturer in the 1910s. Or a typewriter manufacturer in the 1980s.

However, what is the difference between a horse and buggy manufacturer losing their job to the automobile industry, an American worker losing their job to offshoring, and a donut shop owner going out of business because “kids these days” prefer to buy healthier juices instead of donuts (if you can imagine that latter one)? All three of them could lobby Congress to act in their defense, the main difference might be who to scapegoat: “unfair foreign competitors”, “automation”, or some culture war grievance. But these are all just market participants who have lost out to others who have found more efficient means of satisfying consumer desires (which themselves can change, as in the last case). To try to save obsolete industries or only highlight the downsides of innovation would be, in essence, to oppose progress itself. As Virginia Postrel puts it in the excellent The Future and Its Enemies:

“[I]f every voluntary experiment must answer the question, ‘'Are you going to affect the way I live?’ with a no, there can be no experiments, no new communities, no realized dreams,” (p.204).

The creative part of creative destruction means that there are often new industries summoned out of the ground, so to speak, for displaced workers to find new jobs in.

At least, in theory. Historically, most “disruptive” innovation was localized to certain industries — the automobile and railroads to transportation, electricity to power generation, etc. The costs of progress were concentrated on a small group of producers in the short run while the benefits were widely dispersed on a larger group of other producers and consumers more broadly over the long run. And there were always new industries to move into that did not require advanced skills (at least initially). Today, some argue that modern disruptive innovations — the internet, software, AI, etc. — seem to be affecting many or all industries all at once. Software is eating the world, etc. And to the extent that new industries are being created on the creative side of the destruction, it may be quite difficult to enter them. It is not as easy as telling a 50-year-old assembly-line worker to learn to code Python and become a software engineer. Skills can be industry-specific, and labor is not as mobile as simple economic models often assume they are. This puts further pressure on the institutions that undergird our labor markets.

So we must contend, as a society, with a number of political-economic questions: why would producers permit innovation or “progress” if it means the possible destruction of their industry? Do we have a moral obligation to insulate workers from the pains of competition that are no fault of their own? How do we secure the gains from trade and innovation without punishing the workers who lose their jobs?

These are questions I pose to several courses that I’ve taught. They do not have easy answers, but I take this fundamental tension as the motivation for a lot of my explorations into more thorny topics like artificial intelligence, universal basic income, and other issues du jour.

“Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production; and the interest of the producer ought to be attended to only so far as it may be necessary for promoting that of the consumer,” An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Book IV, Chapter 9: Conclusion of the Mercantile system

Schumpeter, Joseph A, (1947), Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy.